While I am not much of a movie buff, during the quarantine, my family and I decided to watch Punjabi films. During our hunt for more movies, we came across a film called Lahoriye, a film we remembered my grandfather saying he really liked, and decided that it would be our watch for the day.

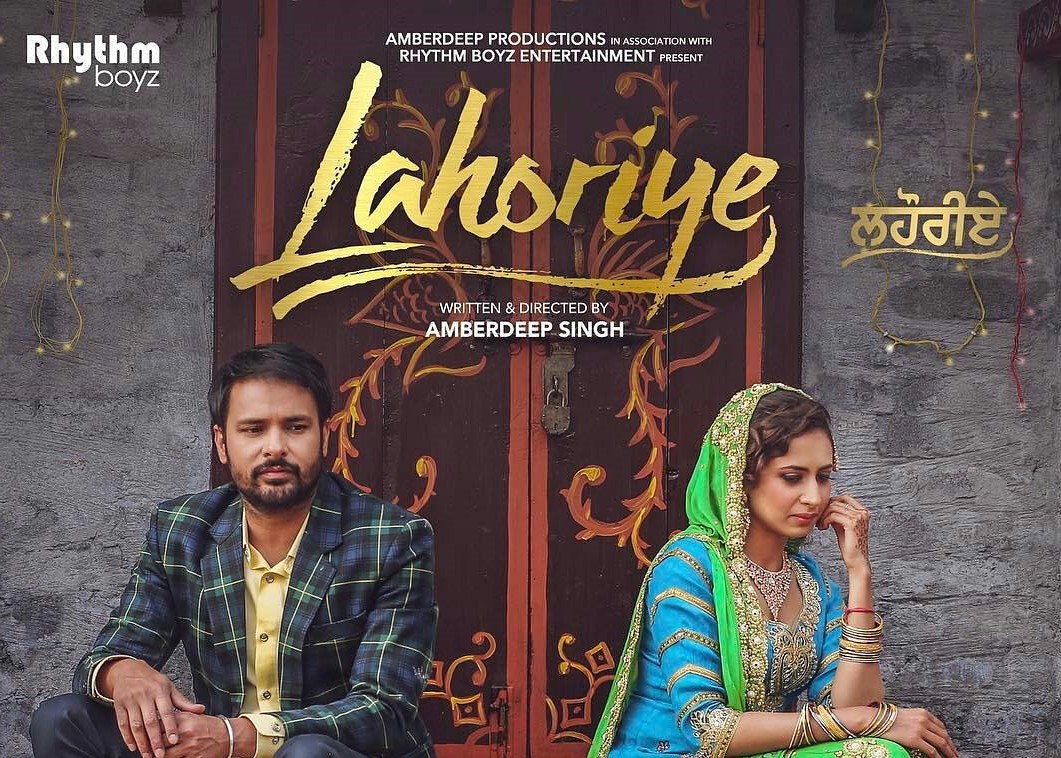

Lahoriye – a 2017 movie that, to an average viewer, would seem like a romantic film with far-fetched drama. But there was a layer to it that was supposed to be an underlying story but overshadowed everything else for me.

The film shows two elderly men, of different families, yearning to catch the feel of the place they were born in and were forced to leave because of a treaty between an oppressor and the governments during the India-Pakistan partition of 1947. The movie begins with a Sikh family trying to safely reach the Indian soil and encountering some Pakistanis, leading to men in their family being killed halfway to India.

To a modern day viewer, this scene might seem like an exaggeration, but I was attached to the film from that scene itself, because I could feel the pain of that family through the experience of my Dadu, who as a boy had to take his two younger brothers and strive to safely elope now Pakistan, the only village that he had ever known and the place which held the memories of his mother, to a completely new part of the world. A boy who had to take care of himself and his brothers in this new place, because his father would only be able to join them on the Indian side later, a fate which was also clouded by uncertainty. A boy who had seen similar funeral pyres and thousands of beheaded, torn, mutilated bodies just at the age of 15. A boy who had to navigate through that horror and take his brothers to safety.

And just thinking about it while watching the film gave me goosebumps. To have seen something like that at such a tender age, having to relive that horror for the next 70 years of his life is something I can’t even comprehend. I often wonder what he must have felt like, waiting on the platform on the Indian side for his father’s train, only to find that it was attacked midway and all the passengers were slain. The horror of seeing those corpses strewn about in the coaches must have shocked him to the core, and the relief of finding that his father had missed his train must have made him cry. And the impact of that feeling, those fleeting moments would have been so crushing, that I still to this day wonder how he found it in himself to get up and carry on with his life.

At this point, I zoned back to the film because just imagining being in his situation was crushing me and I needed to distract myself.

On the screen, the remainder of the family reaches India and goes to live in a village close to the border on the Indian side, taking over a haveli that is seemingly empty, save for one scared Muslim boy, who is yet to cross the border to Pakistan and is scrambling for ways to do it safely. A small boy in the Sikh family, named Hajara Singh, finds him hiding in a room, and the Sikh family gives him a spare turban for safety, if the need arises. As the Muslim boy is leaving, he tells Hajara that if he makes it out alive, he will return to meet him and to see his haveli, the home he has always known.

All of this forms the first 10 minutes of the movie, before it rapidly takes a leap to when both these little boys have families of their own, having now become grandfathers and even great-grandfathers. The initial gag in the film is Hajara Singh resorting to dramatic measures to stop his family from renovating the haveli.

Soon after, the focus of the movie shifts to a cross-border romance between Hajara’s grandson Kikkar, and Ameera, the granddaughter of the Muslim boy Hajara had met all those years ago. Extreme coincidences, because it is still a movie after all.

What ensues next is a series of efforts by Kikkar to woo Ameera, and it takes him to Pakistan. Much like a fairy tale, it turns out that Ameera also likes him and they hilariously convince her family to agree to wed her to him, despite there being a difference in their religion as well as their countries.

Once Ameera’s grandfather gets to know that the boy is from Hajara’s family and realises that Hajara never let anyone demolish that haveli because of one promise made in 1947, his eyes tear up with a kind of nostalgia that I had seen on a different face all my life. He is then convinced that Ameera should marry Kikkar, so that she could live in the haveli that was once his.

This reasoning irks some people at a later stage in the movie, which often showed the characters around the old men get frustrated at their constant state of nostalgia and yearning to go back to the land they belonged to. I could understand the frustration of the family, but I could really feel the yearning of the two men, in both of whom I saw Dadu.

The suffocation of having lost one’s home and struggling the entire life trying to find it elsewhere is something I saw him doing all my life. And I only related to his yearning once I went to Kottayam and found a whole new family in my friends and the people there. I lived there for all of 10 months and I haven’t been able to get over it yet, so much so that I have asked my friends at least 10 times to plan a trip back to Kottayam. And it is not like my life changed once I returned. I just came back home, to the life I always knew, back to my family. And yet, I yearn.

And so, everytime I think about what he had to leave behind, I can imagine the pain he must have felt, the nostalgia that would have overwhelmed him to such an extent that he would have found it hard to grasp his way back to reality and make sense of where he was and why he was forced to abandon his childhood for a life he did not even ask for. That thought makes me cry inside for the grief that I had never experienced but was the only thing he knew. The fact that he lived with that grief and still managed to take care of himself, his brothers, his father and make sure all his children had everything they needed and wanted and then did the same with his grandchildren makes him the strongest person I have ever known.

With tears already threatening to fall, I started watching the movie again where meddling politicians and misunderstandings lead to the wedding being called off, and ultimately it hinges on just one condition – Ameera’s grandfather finding his haveli on his own from the entrance of his old village on the Indian side. But there’s a catch – he would have to be blindfolded for it. As he walks through the streets with a blindfold on, reaching his haveli, it can seem like an exaggeration to some.

But all that went through my head at that time was the accuracy of it. I had once decided to use Google Maps to look at his village in now Pakistan while Dadu was talking about it. He was remembering all the streets and the landmarks that marked the village when he left with that faraway look in his eyes that he always got when he spoke of his previous life. On my laptop screen, I traced every street, every landmark he mentioned and the streets he spoke of helped me trace what was once his home. All without him even knowing that I was looking at the village map while he reminisced.

And once I showed him his beloved house on the screen, the tears and nostalgia in his eyes moved me. Dadu spent hours looking at his old home, showing me the street where he used to play, the houses of his friends and the school he studied at, all the while with his eyes twinkling with fondness, reverence and grief. And what bound me the most to this movie was this same expression staring back at me from my TV, and for a moment, I saw Dadu.

I am no one to critically analyse the acting of a person on screen, and nor am I here to do that. I also don’t much care that the film was supposed to be a romcom against the backdrop of partition.

To me, it became really special because my grandfather could only ever tell his story to the few near and dear ones, but the movie laid bare his tale for everyone to see, feel and realise that the India-Pakistan partition is not just a chapter in the coursebooks.

It is something people experienced, something people lived through, something that took away from them, for a little while at least, their identity. And it gave those people the feeling that they are not alone. For that last one month of his life, my Dadu did not have to feel like he was alone in his state of constant nostalgia and yearning. Even if in just a movie, he found companions. And for that, I will always hold this film close to my heart.

Beautifully written. As a granddaughter who spent much of her childhood listening to her grandparents’ stories of what once was, I think the review does a fabulous job recounting the experiences of so many.

Inspired to see the movie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully written piece ❤️ it encapsulates so many emotions. After reading this I am definitely going to watch the movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person